Hollywood writers say AI is ripping off their work. They want studios to sue

- Share via

When the Writers Guild of America approved a contract with major studios in 2023, ending a 148-day strike, the union became the first bargaining group to gain significant guardrails around artificial intelligence in Hollywood.

But as AI innovation continues to advance, writers say they need more protection from studios. Now, they’re urging entertainment companies to take legal action against AI firms that they allege are using writers’ work to train AI models without their permission.

John Rogers, a 58-year-old screenwriter in L.A., has spent years co-creating the world of TV drama series “Leverage.” After experimenting with ChatGPT, Rogers said he and the show’s creative team suspected that 77 episodes of the series — or five years’ worth of work — had been ripped off and used to fuel AI.

Rogers said that in 2023, after generative AI took off as a mainstream business, he asked ChatGPT to suggest an episode plot for “Leverage,” a modern day Robin Hood story about a former insurance investigator who works with a team of criminals that steals from unscrupulous rich people and compensates those they have hurt.

Without Rogers prompting the chatbot with character names, ChatGPT suggested a plot idea about taking down a corrupt CEO using characters from the show on its own, Rogers said.

Then he found out that scripts for “Leverage,” along with other shows Rogers was involved with, including 2007’s “Transformers” and the TNT series “The Librarians,” were included in a database that was used to train AI models. That data set had subtitles from OpenSubtitles.org, a website that provides subtitles to movies and TV shows in different languages, according to a November story from the Atlantic.

“I’m angry at the absolute arrogance of these companies,” Rogers said. “These companies have gotten hundreds of billions of dollars of value that would not exist if not for our work.”

The guild sent a letter in December to leaders at major studios, including Netflix, Amazon MGM Studios, Sony Pictures Entertainment, Paramount Global, NBCUniversal, Walt Disney Co. and Warner Bros. Discovery. When reached by The Times, those studios either declined or did not respond to a request for comment on the guild’s letter.

So far, no major studio has filed a lawsuit against any of the big AI companies, despite the writers’ complaints. There have been no publicly announced content licensing deals with AI companies, but some major studios have held discussions with AI firms about the technology, causing concerns among Hollywood talent that more of their jobs will be automated to save money.

“The studios own the copyrights to our material that’s being stolen, so they have grounds for legal action, and that’s why we wrote the letter,” Meredith Stiehm, president of the WGA West, said in an interview. “Frankly, they’ve been negligent. They have not protested the theft of this copyrighted material by the AI companies, and it’s a capitulation on their part to still be on the sidelines.”

As AI technology advances, industry observers expect to see more deals between tech companies and studios and talent. But major challenges remain.

The tensions come as the contract between the guild and the Alliance of Motion Picture and Television Producers is set to expire in May 2026. Intellectual property rights and AI will surely be an important element in the upcoming negotiations, said David Smith, a professor of economics at the Pepperdine Graziadio Business School.

“They’re highlighting that it’s going to be a central concern, a key issue that is going to determine how negotiations go,” Smith said regarding the WGA’s letter.

Many writers, including Rogers, Stiehm, “The Killing” creator Veena Sud and “Grey’s Anatomy” co-creator Shonda Rhimes, were listed in a database that the Atlantic created to show what subtitles were used to train AI models from companies, including Facebook owner Meta and Anthropic.

“I’m stunned, disgusted, horrified at what is essentially straight-up plagiarism,” Sud said in a statement. “These AI developers will keep stealing my and other writers’ words until a court finds it illegal, until the studios take action against this theft, and/or until policymakers require developers to negotiate and pay artists for use of our material. It’s a pretty basic concept: Pay the worker for their work.”

The tech industry has said that it should be able to train its AI models with content available online under the “fair use” doctrine, which allows for the limited reproduction of material without permission from the copyright holder.

“We respect intellectual property rights and believe our use of information to train AI models is consistent with existing law,” Meta said in a statement.

Anthropic did not return a request for comment.

“We build our AI models using publicly available data, in a manner protected by fair use and related principles, and supported by long-standing and widely accepted legal precedents,” OpenAI said in a statement. “We view this principle as fair to creators, necessary for innovators, and critical for US competitiveness.”

The problem is what constitutes “publicly available” and how that material becomes accessible to the AI models.

When a writer sells their work to a studio, the studio owns the copyright to that material. Lisa Callif, a partner with Los Angeles law firm Donaldson Callif Perez, said she believes that studios would have legal standing to sue the AI companies.

“The tricky part is whether or not the studios agree that the works have to be defended,” Callif said. “The studios have a vested interest in these AI platforms being developed and being useful to them.”

The current contract between the WGA and AMPTP contains language to ensure that there is a human writer behind every script. Writers must be notified if they are given research or intellectual property that uses AI, and a writer cannot be made to use AI in their work if they don’t want to, the contract says. But there is nothing in the agreement that addresses compensation when a writer’s work is used to train AI models.

“We didn’t get everything we wanted on training, and that’s why we so urge the studios to do something about this scraping of our material,” Stiehm said.

The AMPTP declined to comment for this story.

Some studios are working with AI companies as they look for ways to cut costs. For example, “Hunger Games” studio Lionsgate has a partnership with New York AI company Runway to create a new model for Lionsgate to help with behind-the-scenes processes such as storyboarding.

Tech giants like Amazon (which operates the Prime Video streaming service and MGM Studios) and YouTube parent company Google have invested billions of dollars in Anthropic. YouTube last year unveiled a feature for its video creators to help them brainstorm ideas.

Under the terms of the WGA’s new contract, AI is here to stay — with limits.

Companies want to use artificial intelligence but are also wary about upsetting Hollywood talent.

OpenAI has been in exploratory talks with studios about how they could use its text-to-video tool Sora, according to an OpenAI partnerships lead who wanted to speak anonymously because the discussions are ongoing. Sora has been used to make music videos, commercials and short films. The discussions have not involved licensing whole libraries of content, this person said.

OpenAI has met with Warner Bros. Discovery and Disney, according to several other people familiar with the matter who declined to be named because they weren’t authorized to speak publicly.

A behind the scenes look at a film gala held in San Francisco that screened movies made with artificial intelligence.

Suing the AI giants would be expensive and time consuming. Countries around the world have different rules for copyright holders, making the legal landscape challenging.

Nonetheless, AI companies are facing several copyright lawsuits from publishers such as the New York Times and music giants, including Universal Music Group.

Many news outlets are already dealing with declining revenue from digital ads and subscriptions. Now, their business models are poised to be disrupted again by AI.

The results of the pending cases will help guide other entertainment companies’ next moves, experts said.

“It has massive implications in the industry,” said media lawyer Kailin Che at entertainment law firm Feig/Finkel. “I think everyone’s gonna wait and see what happens there.”

On Tuesday, a judge ruled in favor of Thomson Reuters in its lawsuit against AI startup Ross Intelligence, which it accused of reproducing work from its research firm Westlaw, according to reports. The judge rejected Ross’ possible defenses, including on “fair use.”

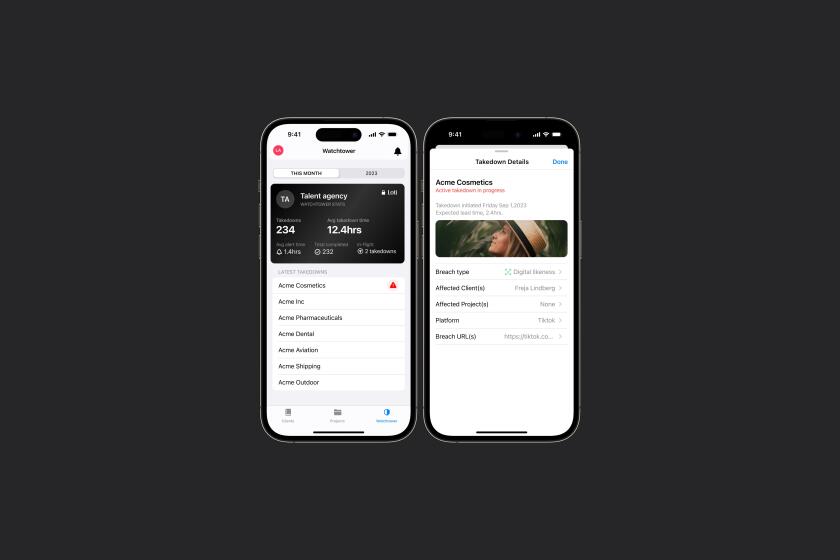

WME is partnering with Seattle-based AI and image recognition company Loti to stop unauthorized digital use of images from WME clients, including deepfakes.

OpenAI on Monday said it will release its controversial text-to-video tool to the public with different subscription tiers.

John Lopez, a 44-year-old writer who has worked on drama series “The Terminal List” and “Strange Angel,” said he’s worried that up and coming writers will have a harder time breaking in, adding that the technology also devalues the work and artistry of screenwriting.

“This was blood, sweat and tears and work and love, and it was transformed into just value for them,” Rogers said.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.