- Share via

In 2020, Travis Flores became one of only a handful of people in the world ever to receive a third double-lung transplant. Diagnosed as a baby with cystic fibrosis, a genetic disorder that causes mucus to build up in the lungs and other organs, Flores had defied doctors’ predictions that he wouldn’t live past age five. At 29, he underwent the rare procedure in hopes of further extending his life.

But as Flores recovered, his thoughts were consumed by another looming battle — this one with actor and filmmaker Justin Baldoni.

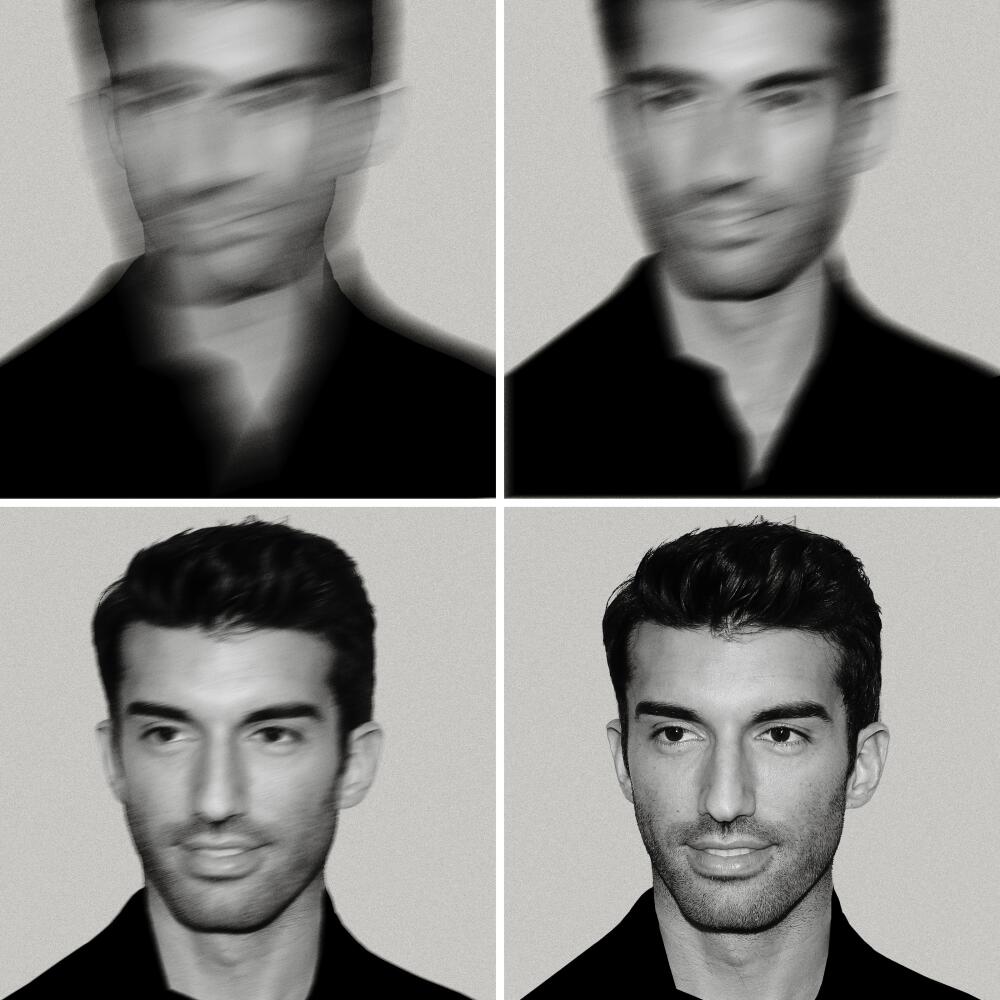

Baldoni, best known at the time as an actor on the CW‘s “Jane the Virgin,” had made his directorial debut in 2019 with “Five Feet Apart,” the story of two cystic fibrosis patients who fall in love. Baldoni said the film was inspired by a different CF activist to whom it was dedicated, but Flores maintained that it bore striking similarities to a screenplay he had written years earlier, “Three Feet Distance.”

“After his third transplant, Travis said, ‘The stress of this is killing me,’” Teresa Flores, his mother, recalled in an interview with The Times. “Through some donations, he got enough money to hire a lawyer.”

In September 2021, Flores sued Baldoni for copyright infringement in federal court. Seven months later, he voluntarily dismissed the lawsuit, telling his family that his legal team advised him that pursuing the case against a high-profile defendant with significant resources would be difficult. Baldoni, who has denied any wrongdoing, was “absolutely not” aware of Flores’ screenplay before making “Five Feet Apart,” a spokesperson for the filmmaker and his production company, Wayfarer Studios, told The Times.

Despite its dramatic elements — a terminally ill man alleging a director appropriated his story for a hit film — Flores’ lawsuit barely made a ripple. Copyright battles are routine in Hollywood, and Baldoni wasn’t yet a household name. Since 2019, he had increasingly focused on directing and producing earnest, socially conscious fare through the “purpose-driven” Wayfarer shingle. He had also positioned himself as a prominent male feminist ally, delivering a 2018 TED Talk, “Why I’m Done Trying to be ‘Man Enough,’” that went viral, spawning a bestselling memoir and a podcast exploring gender, vulnerability and privilege.

Last year’s romantic drama “It Ends with Us” was supposed to be the culmination of Baldoni’s transformation into a multihyphenate force. The adaptation of Colleen Hoover’s bestselling novel found him directing and starring opposite Blake Lively, a far bigger Hollywood name. Friends with Taylor Swift — who attended last year’s Super Bowl with her — and married to Marvel star Ryan Reynolds, Lively has been famous since “Gossip Girl,” a defining teen drama of the 2000s.

But despite grossing over $350 million worldwide after its August release, the success of “It Ends With Us” has been overshadowed by a bitter, escalating feud between its two stars. On Dec. 20, Lively filed a complaint with the California Civil Rights Department accusing Baldoni of sexual harassment and misconduct during the film’s production. According to the complaint, which was followed days later by a lawsuit in federal court, he allegedly pressured her to perform greater nudity than agreed upon, improvised intimate scenes and retaliated with a smear campaign after she raised concerns.

Baldoni denied the claims, filing a $250-million defamation suit against Lively and the New York Times, which published her allegations. Weeks later, he followed with a $400-million countersuit against Lively, Reynolds and their publicist, Leslie Sloane, accusing them of conspiring to destroy his reputation and wrest control of the film from him. Baldoni’s countersuit alleges that Lively and her team engaged in a coordinated effort to undermine him, including making false allegations of misconduct, spreading defamatory statements to the press and using their influence to pressure the studio to try to remove him from the film.

The Blake Lively-Justin Baldoni legal drama highlights conflicting claims about the tactics used by powerful celebrity attorneys on behalf of their clients.

The scandal has since become a full-blown media spectacle, with competing court filings and publicly surfaced messages fueling an ongoing firestorm. Baldoni’s attorney, Bryan Freedman, who has represented Megyn Kelly, Bethenny Frankel, Tucker Carlson and Don Lemon, has portrayed him as an underdog, arguing that Hollywood power players are attempting to make him, according to his countersuit, “the real-life villain in [Lively’s] story.”

Many who have worked with the 41-year-old Baldoni praise him as an inspiring and generous leader. “He is highly creative and in tune with his spiritual side,” said Melissa Ames, who worked as his personal and executive assistant and credits him with giving her career opportunities she had long dreamed of. “He has a heart for helping others. Working at Wayfarer was one of the best times of my life.”

Yet some former colleagues, in more than a dozen interviews with The Times and a previously unreported 2020 lawsuit against Baldoni and Wayfarer Studios, paint a more complicated picture. Several described a pattern of performative virtue and power plays that, in their view, conflicted with the ideals Baldoni professes to uphold.

“They keep talking about [the Baldoni-Lively battle] as David and Goliath but that’s just not my experience,” said one former collaborator, who like numerous others interviewed by the Times declined to be named out of fear of being drawn into litigation. “Justin has a lot of power and a lot of money, and he is not afraid to use them to get his way. We need allies, but we need allies whose personal and business dealings align with who they say they are.”

Through a spokesperson, Baldoni declined to be interviewed for this story, as did Wayfarer Studios’ senior leadership. The spokesperson said the company “has always proudly publicized [its] founding mission of harnessing storytelling to champion inspirational stories that act as true agents for social change, and actively strives to maintain a positive workplace environment that is rooted in this mission.”

Man enough

Baldoni was born in Los Angeles, where his father, Sam, ran an entertainment marketing company, brokering deals to feature brands in movies and TV shows. But after a series of earthquakes and wildfires hit Southern California in the early 1990s, the family relocated to rural Applegate Valley, Ore. Raised in a double-wide trailer in a blue-collar conservative town, Baldoni struggled to fit in, torn between his family’s Bahai faith, which emphasizes gender equality and service to others, and the hypermasculine culture around him.

At school, as Baldoni recounted in his 2021 memoir “Man Enough,” he was hazed by older boys who compared the size of their genitals in the locker room, snuck pubic hair into his food and gave him the nickname “Balboner.” “These types of memories were catalysts for the inferiority complex that plagued me through most of my adolescence and into my twenties, and one that I still battle with today,” he wrote.

As a teenager, Baldoni turned to pornography as a coping mechanism, watching sex scenes from movies and other adult content alone in his room whenever he felt “lonely, insecure, anxious, or even bored.” Years later, in Hollywood, he found himself working alongside actresses he had once fantasized about. “Some of the weirdest moments of my life have happened in the past few years as my teenage fantasies have merged with my midthirties professional life, and some of these women have become friends,” he wrote in “Man Enough.”

Because of his Bahai faith, which discourages premarital sex, Baldoni remained abstinent until his freshman year at Cal State Long Beach, where, as he later recalled in “Man Enough,” his then-girlfriend initiated intercourse without his consent, an experience he said left him privately anguished. “Who was I ever going to be able to talk to about it?” he wrote, picturing an uncomfortable conversation with his “typical bro” roommate. “‘Hey man, so my girlfriend put me inside of her and I wasn’t ready to have sex and I’m feeling really weird about it.’”

After discovering the same girlfriend had been cheating on him, Baldoni later recounted, he spiraled into depression, losing 20 pounds and sleeping on a couch in an empty office his father kept. Seeking support from the Bahai community in Los Angeles, he gradually regained a sense of purpose and threw himself into pursuing a Hollywood career, eventually landing roles on shows like “The Young and the Restless,” “Charmed” and “Everwood.”

By 2013, frustrated with the limited, often superficial parts he was being offered and facing foreclosure on his home, Baldoni began shifting his focus to directing and producing. That year, he founded Wayfarer Entertainment, where his father, Sam, held a role as an executive producer, aiming to create socially conscious content inspired by their shared spiritual values. The company’s first office, located above a carpet business in the Fairfax District, was modest, staffed by “an army of interns around a ping pong table,” recalled Mikey McManus, who described himself as Wayfarer’s first full-time employee.

“How do we use media to make the world a better place? That was the mission,” said McManus, who served as the company’s EVP of Development for its first couple of years. “It was an uphill battle to go into a network and do something wholesome.”

One of Wayfarer’s first projects, “My Last Days,” a web docuseries about terminally ill individuals embracing life, found a home on Baldoni’s friend and fellow Bahai devotee Rainn Wilson’s SoulPancake platform. The series drew millions of views and would eventually land a spot on the CW.

In 2014, Baldoni landed his breakout role as Rafael Solano in the CW dramedy “Jane the Virgin,” based on a Venezuelan telenovela. The role of love interest to Gina Rodriguez’s Jane had originally been intended for a Latino actor but was rewritten as Italian after Baldoni was cast. Years later, Baldoni grappled in his memoir with the systemic racial inequities that he now recognized had given him a leg up. “I can absolutely see how I took a role from a Latino actor,” he wrote. In a chapter devoted to the subject of race, he added, “The system doesn’t benefit me just because I am a man; the system also benefits me because I am a white man (not to mention, an able-bodied heterosexual cis white man from a middle-class family).”

As “Jane the Virgin” garnered acclaim, Baldoni leveraged his rising fame to expand Wayfarer, pitching socially conscious content in crowd-pleasing formats — what he called “choccoli,” or chocolate-covered broccoli. He also ventured into tech entrepreneurship, launching two apps: Shout, which promoted online positivity by scoring users’ social media interactions, and BellyBump, which helped women document their pregnancies through time-lapse videos. Neither took off.

“He’s hardcore Bahai, right? And one of the major tenets, as I came to understand it from him, was, ‘Our work should be our service to mankind,’” McManus recalled. “He used to use this analogy in regards to the patriarchy and the role of women: our species is a two-winged bird and one of the wings has been injured.”

Emerging in 19th century Iran, the Bahai faith now has an estimated 5 to 8 million followers worldwide, including more than 170,000 in the U.S. With an emphasis on racial and gender equality, social justice and global peace, its central goal is to “unify mankind and coexist,” according to Zackery M. Heern, a Middle Eastern studies professor at Idaho State University who is also Bahai. Initially deemed “incredibly radical” for challenging religious authority and advocating social reforms, including women’s education, the Báb — whose teachings paved the way for the Bahai — was executed in 1850 for apostasy and his perceived challenge to the political and religious establishment.

Despite its emphasis on equality, some Bahai principles remain culturally conservative in ways that clash with Hollywood’s more liberal and permissive norms. Women cannot serve on the religion’s highest governing body, the Universal House of Justice, though they can hold leadership roles in all other Bahai institutions. Same-sex marriage is not recognized, as Bahai teachings define marriage as a union between a man and a woman. Alcohol and recreational drugs are prohibited, and gossip — a key currency in Hollywood — is considered one of the most harmful and soul-destroying human traits and strictly forbidden.

It was through his faith that Baldoni connected with Steve Sarowitz, a Chicago-based Bahai convert and billionaire founder of Paylocity, when he served as an advisor on “The Gate: Dawn of the Baha’i Faith,” a 2018 documentary Sarowitz produced about the religion’s origins. The following year, Sarowitz’s investment firm, 4S Bay Partners, acquired a majority stake in Wayfarer Entertainment, establishing a $25-million content fund to expand its staff, move to larger offices and evolve the company — now called Wayfarer Studios — into a hub for socially impactful storytelling.

In 2019, Baldoni made his directorial debut with “Five Feet Apart,” which starred Cole Sprouse and Haley Lu Richardson. Released by CBS Films, the movie grossed over $90 million globally on a $7-million budget, though many reviewers found it mawkish and saccharine.

Encouraged by the film’s financial success, Wayfarer expanded into larger projects, including Baldoni’s second feature, “Clouds,” a 2020 Disney+ drama about Zach Sobiech, a teenage singer-songwriter who died of cancer in 2013. The unabashedly heartstring-tugging film earned solid reviews and propelled Sobiech’s song of the same title to the top of the iTunes chart, helping to raise funds for osteosarcoma through the Children’s Cancer Research Fund.

While building Wayfarer, Baldoni was also shaping his public image as a feminist ally. The birth of his daughter Maiya in 2015 had prompted a deeper reflection on gender equity and the kind of man he wanted to be. In his 2017 TED talk, he declared, “I believe that as men it’s time we start to see past our privilege and recognize that we are not just part of the problem — fellas, we are the problem.”

Baldoni had already demonstrated his love of grand gestures, particularly when it came to romance. Years earlier, he proposed to his wife, Swedish actress Emily Baldoni (née Foxler), with an elaborate, highly produced 27-minute video featuring hidden cameras, choreographed flash mobs and a montage of their relationship — an over-the-top spectacle that quickly went viral.

The TED talk resonated, earning nearly 9 million views, and laid the groundwork for Baldoni’s 2021 book “Man Enough” and the subsequent podcast of the same name.

“The original idea was to make ‘The View’ for dudes,” said McManus. “We wanted a show about men and the things that men don’t talk about, because that was our way of upending the patriarchy — which is destroying our planet.”

‘It was constant positivity all the time’

While Baldoni’s openness about his efforts to be a better man earned praise from many, others questioned his authenticity. Inspired by his faith, Baldoni had long tried to help others through such efforts as the Skid Row Carnival of Love, an annual event he founded in 2015 to help L.A.’s unhoused community. But to some observers his public gestures — such as filming himself giving clothing to a homeless man or asking employees to sign their emails with the phrase “so much love” — felt performative, aimed at self-branding as much as bringing about genuine change.

“It was constant positivity all the time — I would say toxic positivity,” said one former Wayfarer staffer. “I’m always a little dubious of people who advertise themselves as disruptors of the status quo or quote-unquote ‘good people.’ It felt phony.”

In response to these criticisms, a spokesperson for Baldoni and Wayfarer said, “There have never been any reported complaints regarding the workplace culture, or any communicated issues regarding the platforms of its founders. If any guidance was ever provided to employees of how to conduct their written correspondence, it was to ensure that the activities of its employees remained professional and aligned with the ethos of the company. Wayfarer believes that joy and positivity are the essence of good work, and they stand by this statement.”

Multiple employees also expressed discomfort with the increasing prominence of the Bahai faith in Wayfarer’s office culture. “There was an evangelizing aspect to the way Justin spoke about the faith that, in my opinion, felt professionally inappropriate,” said one former employee. Others described a workplace where Bahai principles were frequently invoked in discussions about the company’s mission and projects, particularly after Sarowitz became more involved.

“Bahai values were a driving force behind everything they did,” said another former employee, who wasn’t as bothered by the focus on the faith. “It came up routinely. As a newer Bahai member, Steve wanted to talk about it all the time.”

A spokesperson for Baldoni and Wayfarer noted that, while the founders of Wayfarer Studios are Bahai, the majority of its senior leadership and staff are not, and no Bahai-related activities are ever mandated by the company. “As all of Wayfarer’s projects are rooted in a belief system that stems from various faiths and backgrounds, speaking from a place of spirituality is commonplace,” the spokesperson told The Times. “Employees are encouraged to celebrate and practice their individual beliefs however they see fit, a message which is proudly supported by leadership.”

Rooted in his spiritual beliefs, Baldoni saw Wayfarer as a vehicle for inspirational storytelling, but some employees felt its relentless emphasis on uplift sometimes veered into discomfiting territory. Two former staffers, in particular, spoke of their unease with Baldoni’s repeated focus on stories of terminal illness, which included a 2015 documentary he directed about “The Simpsons” writer Sam Simon that aired on Fusion just a week after Simon’s death from cancer. “‘The message was always, ‘These people are dying and they still have a positive outlook, so everyone has a reason to be positive,’” one former Wayfarer staffer said. “But, you know, you’re also making money off these people, so it feels at least slightly exploitative.”

Reviewers have raised similar concerns. “While it is a spectacle for a good cause, it is still a spectacle,” Variety wrote of “My Last Days,” “and one that sometimes is guilty of reveling in its own self-satisfaction.”

Responding to these concerns, a spokesperson for Baldoni and Wayfarer said, “It is a shame that anyone would criticize the platform that Mr. Baldoni and Wayfarer Studios have given to these communities of people living with chronic illness, who are in desperate need of the critical funds and global awareness that each one of these projects directly provided. Since before Wayfarer was even founded, Mr. Baldoni dedicated his professional career to raising awareness and funds for these individuals with the sole intent of memorializing their legacies.”

While some former employees voiced concerns about aspects of Wayfarer’s workplace culture, others described positive experiences with the company. Australian-born filmmaker Christel Cornilsen, who began working with Wayfarer in 2014, became the first female director on one of the company’s projects when she replaced a male filmmaker who had dropped out of a documentary shooting in Malawi. The shoot proved arduous, with no electricity or running water, but Cornilsen praised Baldoni and Wayfarer for their steadfast support.

“I was stuck in the middle of nowhere dealing with this anarchy and they were really there for me,” Cornilsen recalled. “They risked a lot of money for humanitarian projects that they didn’t make back. That’s putting your money where your mouth is. There were always good intentions. A lot of corporations are phony. You have to measure the impact. Justin is generally a good egg.”

Following a series of leadership changes at Wayfarer Studios, Jamey Heath — Baldoni’s best friend and a fellow Bahai — became the company’s president in 2021. A longtime songwriter and producer who worked with artists Chaka Khan and Solange, Heath, like Sarowitz, had little prior experience in the film industry. The following year, Sarowitz and his wife, Jessica, invested an additional $125 million into the company, fueling further expansion. In March 2024, Heath, who also co-hosted the “Man Enough” podcast, was elevated to chief executive.

Wayfarer’s internal culture was at times dysfunctional and riven by internal politics, according to one former executive at the company, with Baldoni — who was often away on sets — only occasionally making appearances: “He would come in and everyone would kind of stand and greet him as if he was an arriving conqueror. But he didn’t really understand how the day-to-day business worked.”

A spokesperson for Baldoni and Wayfarer said that Baldoni was not deeply involved in daily management, adding, “Justin Baldoni does not oversee, and hasn’t ever overseen, the day-to-day operations of Wayfarer Studios,” and emphasizing the company’s “robust leadership team.”

Whatever workplace tensions existed came to a head in 2020 and 2021, when a lawsuit alleging racial discrimination and wrongful termination brought internal grievances to light and a separate copyright dispute involving Baldoni and Wayfarer raised questions about whether the company’s stated ideals aligned with its practices.

In Dec. 2020, former Wayfarer executive Shane Norman, who is Black, filed a lawsuit alleging that he was recruited with promises of job security and professional advancement but was later marginalized and ultimately terminated after raising concerns about racial inequities at the company. The complaint claimed that during the hiring process, Sarowitz told Norman “We need somebody here who looks like you,” but after he spoke out — particularly during the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests — colleagues labeled him an “angry Black man.”

Asked about Sarowitz’s alleged comment, a spokesperson for Wayfarer said, “Mr. Sarowitz was not a defendant in the lawsuit. Regardless, Wayfarer Studios, Wayfarer Entertainment, and Baldoni denied this and all the material allegations in the complaint, the First Amended Complaint, and the Second Amended Complaint.”

The lawsuit alleged Wayfarer perpetuated “a pattern of sidelining and tokenizing people of color,” a dynamic that, according to the complaint, was “antithetical to everything Wayfarer claimed to stand for.” It further claimed that after voicing these concerns, Norman was demoted, his pay was cut and he was ultimately terminated, while non-Black employees in similar circumstances received severance packages that he was denied.

Baldoni and Wayfarer denied the allegations. In September 2021, a judge dismissed some of Norman’s claims in the case, and he later filed an appeal. In April 2022, he voluntarily dismissed the lawsuit with prejudice, meaning he could not refile it. A source with knowledge of the negotiations said Norman received approximately $150,000 to drop his claims, though the terms of any settlement were not publicly disclosed.

“Throughout their defense of Mr. Norman’s lawsuit ... Mr. Baldoni, Wayfarer Studios and Wayfarer Entertainment vigorously denied all of Mr. Norman’s claims,” a spokesperson for Baldoni and Wayfarer said. “In fact, public records confirm the trial court dismissed Mr. Baldoni and Wayfarer Studios from the lawsuit well before any resolution by the parties and the concurrent dismissal of the remainder of the lawsuit. Other than stating that the matter was resolved, we are unable to further comment.”

In September 2021, cystic fibrosis advocate and writer Travis Flores filed a lawsuit alleging that Baldoni, Wayfarer Entertainment and other defendants incorporated elements of his 2010 screenplay “Three Feet Distance” without permission into Baldoni’s 2019 film “Five Feet Apart.” According to the complaint, “Three Feet Distance” was optioned by an affiliate of Universal in 2015 but never produced. The lawsuit claims that in 2016, Flores shared his screenplay with a genetic testing company that had expressed interest in the project under a confidentiality agreement, and that an individual with access to the script later consulted on “Five Feet Apart.”

According to the complaint, after Baldoni announced “Five Feet Apart,” Flores was invited to appear on Baldoni’s docuseries “My Last Days.” Flores claimed in the lawsuit that he deliberately avoided discussing “Three Feet Distance” on the show because he was concerned his participation might be used to undermine a potential copyright claim.

Baldoni and the other defendants denied the allegations, and in March 2022 Flores voluntarily dismissed the lawsuit with prejudice. No determination of liability was made.

According to multiple sources, Flores ultimately dropped the case after being advised by his legal team that Baldoni had the financial resources to sustain a prolonged legal fight, and that continuing the lawsuit could take a toll on his health.

In late 2024, months after Flores’ death at age 33, Bryan Freedman — the attorney who had represented him in the case — began advocating for Baldoni in his battle with Lively.

Asked why he decided to represent Baldoni after previously representing Flores in a case against him, Freedman said in a statement, “Over the years, I have learned what great people Justin and Wayfarer are. The [Flores] case was resolved without any determination of liability on Justin’s or Wayfarer or any other defendant’s part. Since then, it has been further confirmed to me that Justin and Wayfarer are exceedingly honorable and highly ethical.”

Some former employees maintain that Baldoni’s intentions were sincere, even as aspects of his leadership drew criticism. “His heart is truly in the right place,” said one former Wayfarer employee. “He’s a young guy who has gained access to a lot of money and has been figuring out how to run the company as he goes. He did a lot of stuff that was really helpful to a lot of people that no one knows about that far outweighs any mistakes.”

One former Wayfarer executive, who requested anonymity to speak candidly, described the challenges of Hollywood’s for-profit progressivism as a constant negotiation between ideals, egos and industry realities: “The social impact model is a tough go in this industry. There’s so much temptation and greed, it’s hard to truly do good.”

The higher the pedestal, the harder the fall

As Baldoni’s battle with Lively unfolded last year, speculation swirled online about a curious parallel on the big screen. In the summer comic-book tentpole “Deadpool & Wolverine,” some viewers wondered whether Reynolds was taking a jab at Baldoni with the character Nicepool, a sanctimonious antihero sporting a man bun. In one scene, Nicepool, also played by Reynolds, comments on the appearance of Ladypool (played by Lively) after childbirth, saying, “She just had a baby too — you can’t even tell.” When Deadpool replies, “I don’t think you’re supposed to say that,” Nicepool shrugs it off: “That’s okay. I identify as a feminist.” Later, Ladypool guns Nicepool down in front of a flower shop — a significant setting in “It Ends With Us” — as Deadpool uses him as a human shield.

Baldoni’s legal team took notice. In January, Freedman sent a letter to Disney and Marvel demanding they preserve all documents related to Baldoni, alleging “a deliberate attempt to mock, harass, ridicule, intimidate, or bully Baldoni through the character of ‘Nicepool.’” Appearing on “The Megyn Kelly Show” on Jan. 7, Freedman highlighted the similarities: “There’s no question it relates to Justin. I mean, anybody that watched that hair bun ... it’s pretty obvious what’s being done.” A representative for Reynolds, who has not publicly remarked on the Nicepool allegations, did not respond to The Times’ request for comment.

Inside Blake Lively’s legal complaint against her ‘It Ends With Us’ co-star and director Justin Baldoni: Who’s who and what you need to know.

The alleged ridicule adds further fuel to a scandal that has already tarnished Baldoni’s reputation and pitted him against one of Hollywood’s most powerful couples. Having been dropped by his agency, William Morris Endeavor, and stripped of a recent award from the nonprofit Vital Visions, which honors advocacy for women and girls, Baldoni has attempted to repair his image by shifting the narrative back to Lively, whose own reputation has also sustained damage.

In recent weeks, several audio and video recordings have emerged that Baldoni’s legal and PR team believes exonerate him, including raw footage from the set of “It Ends With Us.” Around the same time, his team launched a website featuring his court filings and a 168-page timeline of the film’s production and the ensuing dispute, part of a broader push to counter the allegations and shape public perception.

As Baldoni digs in for the battle ahead, the stakes could not be higher. A victory, whether in the court of law or public opinion, could offer a path back to Hollywood. A loss could leave everything he built in ruins.

Even before the current crisis, Baldoni was candid about his fear of losing everything, laying bare his self-doubt and insecurities in the opening chapter of his memoir.

“I am afraid — a lot,” he wrote. “I am afraid of not providing for my family, not being financially secure ... I am afraid of losing my relevancy, of messing up my next movie and going to ‘director jail,’ of gaining weight or not aging well (whatever that means) and then not getting any work as an actor because it had never been my talent that got me the work for all these years but my looks. I am afraid that I will be seen as an imposter and everyone will find out that I’ve just been faking it this entire time and really have no idea what I’m doing or how I even got here.”

Alongside his self-doubt, Baldoni acknowledged another fear: being placed on a pedestal — even one he helped build. “The higher that pedestal gets, the harder the fall,” he wrote. “I hate pedestals.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.