2013 Pulitzer finalist | Feature Photography

Aaron Rubin waits while a caregiver prepares his bed for an afternoon rest before dinner. Rubin, 30, of Escondido, Calif., was debilitated by a prescription drug overdose years earlier, leaving him in the constant care of his parents. Prescription drug abuse is the fastest growing drug problem in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) with prescription painkiller overdoses reaching epidemic proportions. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Liz O. Baylen of the Los Angeles Times for her intimate essay, shot in shadowy black and white, documenting the shattered lives of people entangled in prescription drug abuse.

Once an able-bodied young man, Aaron Rubin now receives full-time care from his mother, Sherrie, his father, Mike, and a handful of caregivers. Before he overdosed on prescription medication, Rubin was socially active, a football player -- and a partier. The brain damage he suffered while in a coma left him confined to a wheelchair, unable to speak and with little control over his body. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Since his overdose, Aaron Rubin has been in physical therapy, trying to regain muscular function and coordination. He is one of a growing number of people who live to tell the story of overdosing. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

“I am sick. I still can’t stop taking pills even after detox. I am in a black hole filled with pain, self-loathing, despair and darkness... I just want to feel normal,” Aaron Rubin once wrote of his addiction in his rehab journal. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

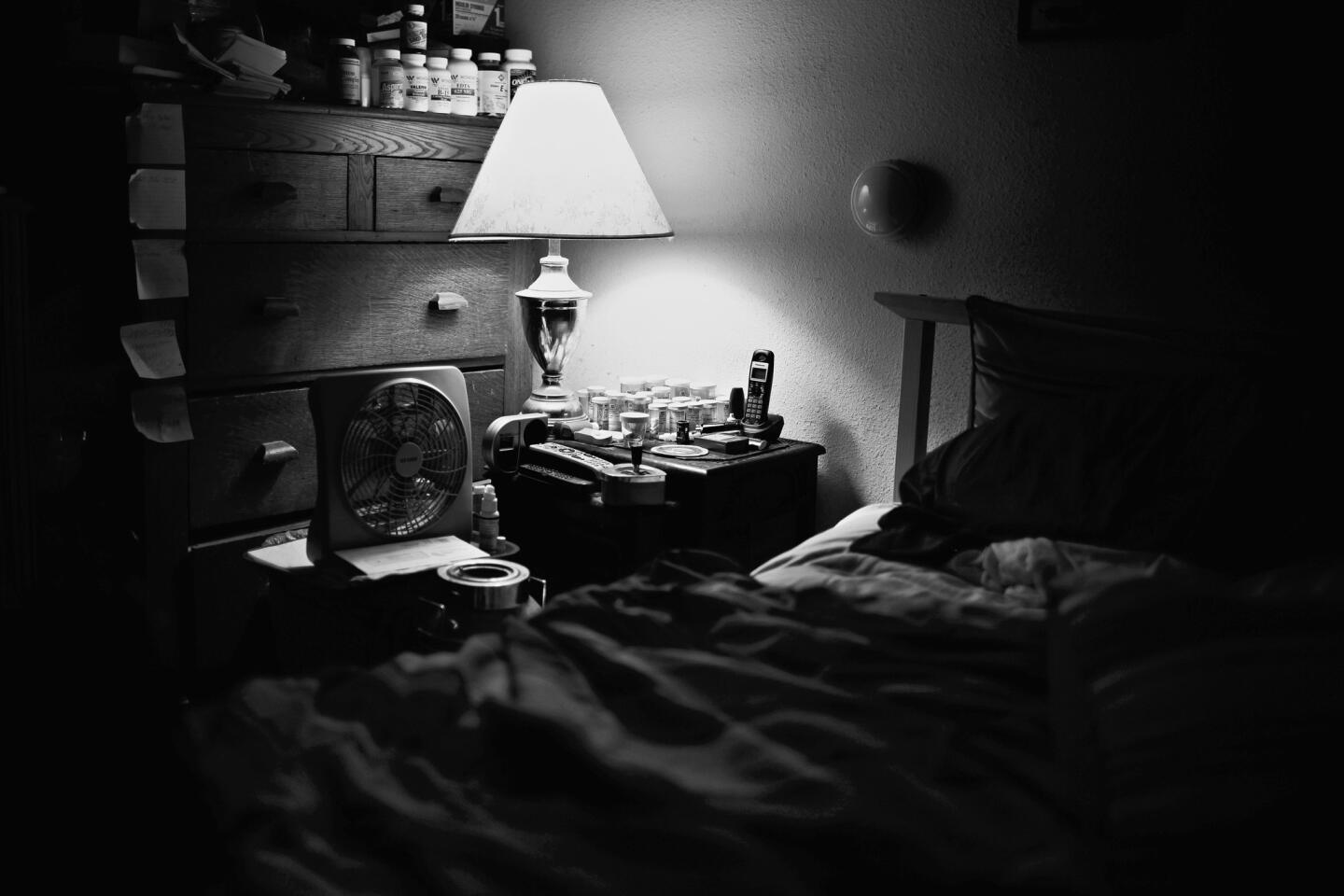

Pill bottles line a dresser and a nightstand in a San Diego home, a scene familiar to many households in which prescription drug addiction has taken hold. About 12 million American teenagers and adults reported using prescription painkillers to get high or for other non-medical reasons in 2010, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Police investigators search a suspected ‘ghost clinic’ in Reseda, Calif. Scammers use such offices to cheat the system, stealing or buying Medicare ID numbers from patients and using the numbers to submit phony claims. This particular clinic was connected with an adjacent medical office suspected of illegal prescribing practices. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

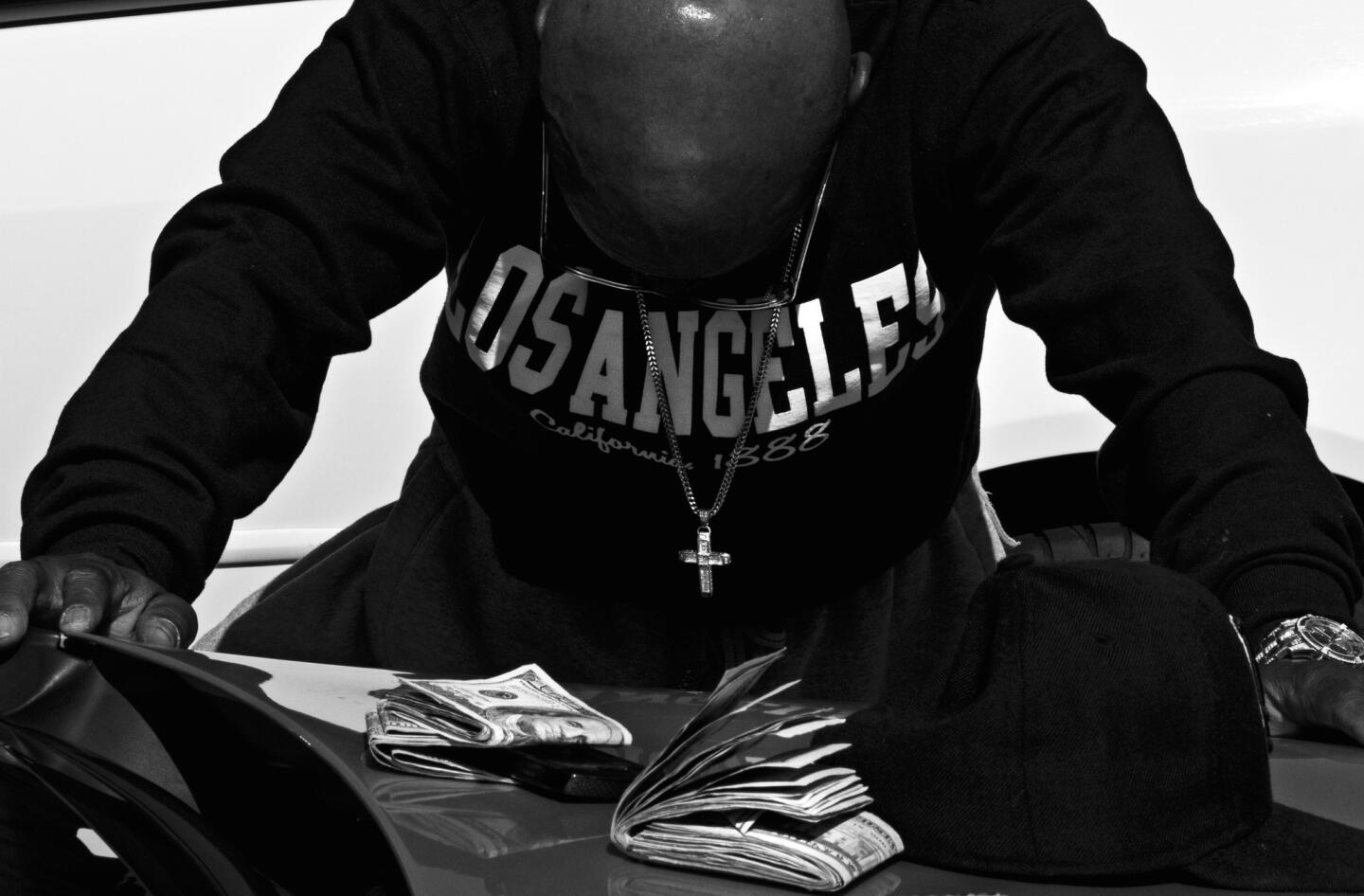

A man is arrested and booked for possession of a deadly weapon and conspiracy to commit prescription fraud outside a medical clinic, according to authorities that raided the office and found the clinic operating without a doctor. Places like these, where people can buy prescriptions without medical exams are called ‘pill mills.’ (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

A woman waits to be questioned by authorities outside a suspected ‘pill mill’ in Sylmar, Calif., during an investigation by the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and other agencies. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Less than four days through his treatment at Malibu Beach Recovery Center, Edward Shut strains to relax in his evening yoga class. “I’m not used to somebody regulating my meds for me. I’m used to, you know, I want one and I take one,” Shut says of the difficulties of detoxification. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

After 10 years of abusing medications, all prescribed by doctors, Edward Shut checked himself into Malibu Beach Recovery Center. He handed his pills to counselors to dole out as they tried to wean him from the substances. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Edward Shut at Malibu Beach Recovery Center. “First the man takes the pill, then the pill takes the man,” a counselor tells Shut. Shut understands this adage intimately as he seeks to regain a life without prescription medication. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

John Jackson, a former stuntman who broke his back on the job, meets with Dr. Julio Diaz during an appointment. Jackson said the Santa Barbara doctor, whom he described as compassionate, gave him back his life by prescribing potent narcotics to help relieve his almost constant pain. (Diaz would later be arrested.) (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

Dr. Julio Diaz is led from his Santa Barbara office after being arrested on federal drug trafficking charges; soon after, his medical license would be revoked. By then, 17 of his patients had died of overdoses or related causes, coroners’ records show. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

In a parking lot outside the coroner’s office in Bakersfield, Calif., Susan and Ray Klimusko see their son Austin for the first time since his overdose death; standing next to them is their son Kyle. Austin’s opiate addiction began with prescription drugs, but ultimately progressed to heroin. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

“As a community we have been quietly suffering, long dreading the worst, and the worst is here,” Susan Klimusko told the City Council in Simi Valley, Calif. “There is no fault here. There is no one to blame. We are all in this together.” Concerned residents and parents including Klimusko and her husband, Ray, center, pack the council chambers to demand that city officials address a spate of drug overdose deaths. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Friends and family sign Austin Klimusko’s casket at his funeral in Simi Valley. “Instead of saying, ‘Have a good year in college,’ now they’re signing goodbye,” said his mother, Susan. “I wanted this to really be a message to his friends who are still using -- how heartbreaking it is. The victims now are really the family and friends left behind.” Susan’s son Austin graduated from abusing prescription drugs to abusing heroin because it’s cheaper and easier to buy. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)

Advertisement

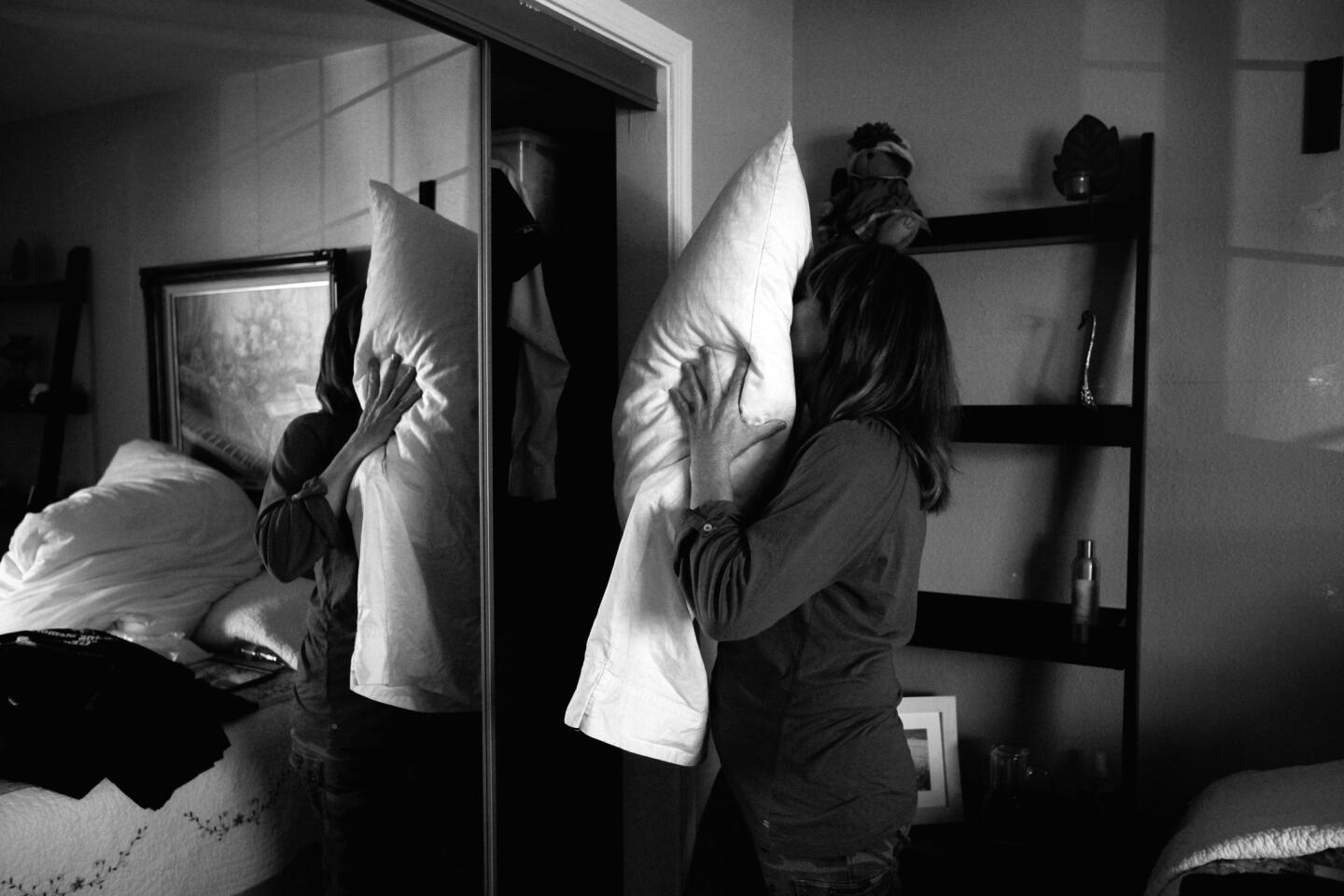

Susan Klimusko saved her sonÕs pillow because its scent reminds her of when he was still alive. (Liz O. Baylen / Los Angeles Times)